Skopje – A Brutalist Beauty in Disguise

To many travelers who make it to Skopje, North Macedonia’s capital feels… underwhelming. Some call it ugly. Others—downright repulsive. The most common take? “A kitschy architectural Disneyland.” Scroll through travel blogs or social media, and you’ll often read that there’s “nothing worth seeing” here. Sure, the charm of the Old Bazaar draws a few admirers—but for many, it’s just not enough.

But for me? Skopje is fascinating. It doesn’t sweep you off your feet like Ohrid. It’s not love at first sight, and honestly—it’s not for everyone. I like to call it the ugliest beautiful city I know. Loving Skopje is not easy. It’s a complicated kind of affection. One that demands effort.

“A city that grows in depth; a city that spreads underground; a city that devours itself.” That’s how Nikos Chausidis once described Skopje—and all of Macedonia, really. On one hand, it’s an “El Dorado for archaeologists.” On the other—an endless graveyard. Skopje didn’t expand outward over the centuries. It layered itself.

One of those layers spans roughly three decades: from the devastating 1963 earthquake to the breakup of Yugoslavia and Macedonia’s independence. For a brief moment, Skopje was internationally praised as an architectural gem. A gem of a style that is now misunderstood and mostly rejected: brutalism.

Skopje – An Architectural Pearl

At first glance, Skopje can feel like organized chaos. The most prominent visual impression? Skopje 2014—a massive redevelopment project (unofficially dated 2010–2017), launched under Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski. The neoclassical facades, countless statues, and an overall “antiquization” of the cityscape have come to define Skopje’s modern image. Tourists are steered toward Ottoman heritage sites, carefully reminded that these are relics of the past—not reflections of the present. Meanwhile, other witnesses of the city’s history are quietly hidden from view.

Almost a decade ago, the then-mayor of Skopje’s Centar district, Vladimir Todorovik, said: “Skopje needs a new image. Instead of a grey, socialist-realist city, let’s give it an aesthetic identity. Let’s transform the city center into a complete architectural and urban whole, something that expresses artistic vision.”

The problem? Labeling Skopje’s postwar style as “socialist realism” is not only inaccurate—it’s unfair. That style barely left a mark on Yugoslavia. After the Tito-Stalin split, Yugoslav planners quickly moved toward modernism. And Skopje was no exception.

Whether you like the city’s old look or not, the postwar period brought plenty of international recognition for Skopje’s public buildings. For a time, the city was hailed as a model of modernist urban planning.

But before that transformation could happen, Skopje—like Chausidis said—had to devour itself.

The 1963 Earthquake

On July 26, 1963, Skopje collapsed like a house of cards. At 5:17 a.m.—the time forever frozen on the clock of the old train station—a massive earthquake hit. Measuring 6.1 on the Richter scale, the quake killed over 1,000 people and left around 100,000 homeless. From the air, the city looked like it had been bombed. The devastation was so great that, for a brief moment, it paused the Cold War. Just days after the quake, Soviet and American soldiers were working side-by-side, clearing rubble.

There was a lot of rubble. While many buildings had collapsed, many more – while still standing – were damaged beyond repair. The structural axes were compromised, so even what stood had to be carefully dismantled bit by bit.

Help poured in from 78 countries, including Poland. And it was the Polish team that played a massive role in rebuilding the Macedonian capital.

The Polish Role in Rebuilding Skopje

Fun fact: Skopje owes the survival of its beloved Old Bazaar to Adolf Ciborowski, a Polish urban planner. Without him, the bazaar might have been lost in the rush to modernize. If you want to know more, check out the documentary Skopje: The Art of Solidarity.

In Yugoslavia, there was never a single national architectural style—on purpose. The government promoted “unity through individuality.” So while some general aesthetics were shared (think: the iconic spomeniks), local expressions were welcomed.

Skopje, now a city of rubble, was a blank slate. That’s exactly how Japanese architect Kenzo Tange saw it—and for a long time, he was credited as the man who “rebuilt” Skopje. But that’s only partially true.

In reality, several teams were involved in the city’s redesign. The Polish team arrived before anyone even contacted Tange. Led by Ciborowski, under a UN mandate, they handled the technical side of the rebuild. Without their determination, things might never have gotten off the ground.

In 1964, during a meeting in Ohrid, the Poles presented their urban plan and were officially brought into the reconstruction process—alongside the Greek firm Doxiadis Associates, who had just won the UN’s public tender.

As for the vision—the symbolic and ideological design of the new Skopje—that was decided through an international competition. Eight teams were invited: four from Yugoslavia (Skopje, Belgrade, Zagreb, Ljubljana), and four from abroad (Rome, New York, Rotterdam, Tokyo). The jury honored two projects. The clear crowd favorite? The one from Tokyo, led by Kenzo Tange. But because it was also controversial, the Japanese team had to collaborate with a team from Zagreb on what would become the “ninth project.”

Just a Shadow of a Vision(er)

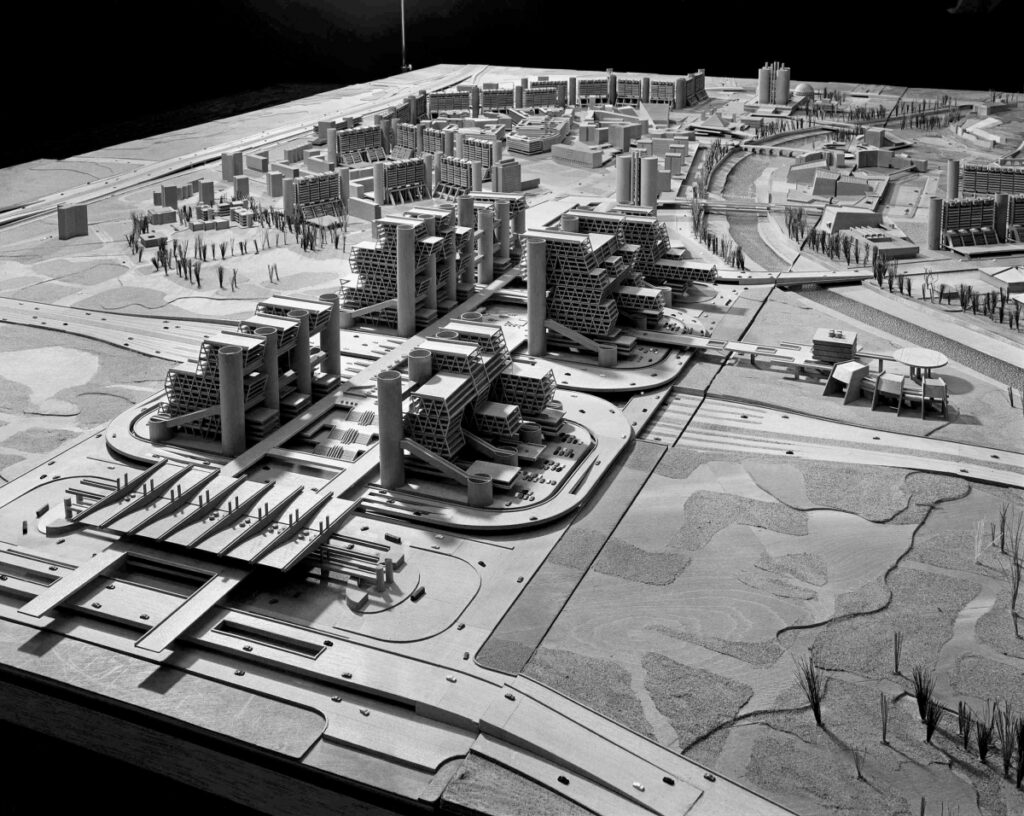

Tange’s design focused on Skopje’s core—about 295 acres between the new train station and what was then Republic Square (now Macedonia Square). His concept was based on two intersecting axes, linking the old and new parts of the city. The east-west axis followed the Vardar River, starting at the new station—the only building from Tange’s plan that was actually built. The north-south axis stretched from the ruins of the old station to the Ottoman čaršija (bazaar).

The train station itself was imagined as a kind of transformer—distributing energy throughout the city. Tracks were elevated several meters above ground to prevent traffic congestion, improving pedestrian and public transport flow.

The Vardar’s banks were to be green spaces. Administrative buildings along the axis formed the “City Gate” into downtown. These included seven-story buildings with offices, cultural venues, restaurants, and shops. The outer belt was reserved for high-rises: business centers and apartment blocks up to 17 stories tall.

Republic Square was envisioned as a place of encounter—both symbolic, where the axes of the old and the new city crossed, and literal, as a crossroads for the diverse minorities sharing the capital’s space. Due to the square’s transformation into an administrative, cultural, entertainment, and business hub, meetings between residents were inevitable. Skopje was meant to become an open city—for everyone, and open to everyone.

The best-realized part of the plan? The City Walls—a ring of residential blocks surrounding the square. It bordered Republic Square to the west, stretched south toward the old train station, and curved in a semicircle to reach the City Gate in the east. Its natural continuation to the north was the bazaar, watched over by the hilltop fortress. Like a fortified rampart, it encircles the city center—a living (and inhabited) structure that both protects and absorbs history and tradition. Individual stairwells are separated by vertical communication shafts, reminiscent of towers. The ground and first floors were designated for shops and service premises. Balconies on the first floor hover above the sidewalks, creating the illusion of tunnels—like covered passageways. Each block was surrounded by space for greenery, recreation, and parking.

Though enthusiastically received, Tange’s plan was only partially implemented. The Japanese visionary’s urban layout was retained, while only one architectural element—the train station—was built, and even that not in its entirety. The City Wall preserved the spirit of the original concept, but the final appearance of the buildings was given by Yugoslav architects. As Tange himself once said, speaking of what remained of his idea in Skopje: it was “only a shadow, barely visible in the moonlight.”

Brutalism and Yugoslavia

Brutalism—often labeled the “extreme modernism” of the postwar years—emerged as a raw, radical branch of late modernist architecture. Today, many see it as cold, even monstrous: grey concrete masses with exposed structural elements and unapologetically visible pipes and joints. Yet half a century ago, these very same features evoked something entirely different: hope, progress, honesty. Brutalism was about function, space, and truth to materials. In many ways, it wasn’t so far removed from the minimalist aesthetics so celebrated today.

The founding myth of brutalism begins with Le Corbusier, who saw in raw concrete something deeply human and profoundly natural. He admired its coarse texture, comparing it to the irregularity of unhewn stone. He likened imperfections in its surface—air pockets, stains, rough patches—to wrinkles and birthmarks, the very features that make each human face unique. For him, béton brut wasn’t merely a material; it was a skin.

Brutalism reached Yugoslavia relatively early—by the 1950s—and found fertile ground. It resonated with Marshal Tito’s political vision of “unity in individuality,” a project of forging collective identity while accommodating (or containing) national distinctiveness. In architectural terms, brutalism provided a new visual language: strong, monumental, unapologetically modern. It was a turn toward the future, toward innovation and universalism, away from regionalism or ethnic kitsch.

Skopje, especially after the 1963 earthquake, became a playground for this new architectural ideal. Dozens of celebrated brutalist buildings rose from the ruins, earning the city multiple international awards. Architects from across Yugoslavia contributed to reshaping the capital—but not only them. One of Skopje’s most iconic structures, the Museum of Contemporary Art, was designed by the acclaimed Polish trio known as the “Warsaw Tigers”: Wacław Kłyszewski, Jerzy Mokrzyński, and Eugeniusz Wierzbicki.

Brutalism in Skopje – A Map

Following the traces of Skopje’s brutalist heritage today is no easy task. At best, these buildings are neglected, left to fade behind billboards or wedged between gaudy new developments. At worst, they’ve been quite literally buried—under layers of cheap styrofoam, plaster, paint, and plastic. These makeshift facades, mimicking classical architecture, are not restorations but erasure by disguise.

In the 1990s, several parts of the former Yugoslavia underwent what architect and researcher Arna Mačkić calls a “war against architecture.” Buildings symbolizing the Yugoslav ideal—of solidarity, shared identity, pan-national culture—were systematically destroyed. In Macedonia, the cleansing of this architectural memory came later, with the launch of the Skopje 2014 project. Many award-winning brutalist structures were then boxed up in pseudo-baroque shells.

More than a decade after the change in government and the official suspension of the project, the legacy of Skopje 2014 still sparks heated debate. Art historians, urban planners, and residents alike are left to grapple with a difficult question: how do we remember a city whose memory has been forcibly rewritten? To forget part of the past is to rupture collective identity. But equally, the structures imposed by Skopje 2014 are now part of the city’s lived reality. They shape how locals see themselves—and how outsiders see Macedonia.

So the question lingers: What matters more—the architecture beneath, or the shell above? Or perhaps neither? Or both?

Whatever your answer, I invite you to walk the brutalist trail of Skopje. Here you’ll find a [Google Map link] marking over 30 buildings. Click on any point to learn when it was built and who designed it—then go out and meet these concrete witnesses of a forgotten future.